It's been almost a month since last I updated the blog. I apologize. Much has transpired in the interim, including a hiking trip with ESS, a trip to Japan to visit my sister, and the beginning of the World Cup.

Why has it been so long since my last update? Why can't I just sit down and jot a few notes down once a week? I know so many blogs where the owner starts them with good intentions and ambitious updating goals, but over time the updates start to fall off, if not stop completely.

There are many factors that contribute to an intermittent blog. It takes a lot of time to sit down, organize one's thoughts into a coherent document, not to mention toning, uploading and organizing the photos. Beyond the commitment of time and energy lies the problem of content. Perhaps for you, SoKoNotes remains a source of interesting anecdotal reporting on another part of the world. Perhaps there is still a sense of wonder and excitement. I remember feeling that, too. In the first half of the year it was strong.

However, the feelings of "new and exciting" have naturally subsided over time, giving way to routine and the personal patterns into which I think all people settle over time. These contented patterns are subtle assassins. They smother creativity, strangle the desire to explore new places and blindfold the clear eyes one needs to see the world in fresh new ways. To me, a routine is a kind of social entropy, a tendency for people to find the easiest, most hassle-free path through life like water finds the easiest route down a mountainside.

Perhaps its because life just feels too big. Perhaps its because there is simply too much to explore and know (and this overwhelms people). Perhaps it just makes more logical sense to walk the quickest way to the busstop day-in and day-out. But what did I not see this morning? What did I miss by going home the same way every night for two months? Worse yet, what child have I left behind as I fine-tune my lesson plans to fit the majority of the class? Of the troubled students, the ones with learning disabilities or behavior problems, which of these children are lagging as I trim back the energy I once used to help them?

I fight against these entropic enemies by willingly changing patterns, trying new things, and hanging out with new people. In my classes I teach from different angles, I talk to Gavin about his ideas, and I keep an ear open to the children. Every week I sit down and assess each class in my notebook, identify problems, narrow down what worked and with whom and customize my next lesson to that specific group of children. I even bring a little creativity to bear on the deadly routines themselves, such as here, right now, in this blog. I explore them and think about them.

But like any fight against entropy, all of this requires a lot of energy.

I find the slow slip into routine to be the strangest, most eye-opening part of this chapter in my life. It gives me pause and makes me postulate that, given enough time, a person could get used to any sudden change in life, even those as radical as prison time or floating adrift in a life raft for months. That's the positive side of routine, I guess. One the other hand, how much of my life could have been more interesting if I had just answered that email from someone I just met, walked that blue-blazed trail, or opened my mind to some strange, radical new idea. My days in Korea have become as comfortable as any I lived in the States. There are still serious challenges that I haven't properly addressed, such as the language barrier, and the seed of homesickness has blossomed and grown around my soul like an ivy creeping up the trunk of a tree. But these are problems that have a clear solution: Go home.

Home.

last week I explained the difference between the words "home" and "house" to Advanced Three. A house is a structure, I explained, like an apartment building or a wood hut. A home is where you live. To help clarify the distinction, I had two students; one who lived in a house and one who lived in an apartment, stand up. I pointed to one and said, "Her home is an apartment building" and "his home is a house."

"Teacher, where is your home?" Jin-soo asked.

"I live in Dongsamjugong apartments," I replied. Jin-soo paused, as if confused, and looked around at the other students, who seemed to know where he was going with the question and remained quite. He cocked his head at me as if about to speak, but Han-sol beat him to the punch.

"Teacher, is your home America?" Han-sol shot from off to my right, picking up and echoing Jin-soo's line of reason. I think she meant to ask, "teacher, isn't your home in America?" But her level of English isn't quite up to affirmative questions asked in the negative form of the verb. I knew what she meant. My heart seized and thoughts of my parents, my sister and my friends flashed across my mind. I smiled.

"Yes," I said. Ju-young, the tallest girl in the class, piped up.

"Do you miss your family?" She asked.

"Yes," I again replied, my voice getting softer. The line of questioning broke off, but I could tell something had been confirmed in the students' minds. They looked at one another in silence. There was nothing malicious in their inquiry, but rather curiosity, even a little sympathy. These children were instinctively aware of the outward signs of homesickness, and it seemed to fascinate them. They had obviously seen it before, perhaps in other native speakers before me.

I don't think people give children enough credit. I think they have senses that adults have lost or neglected. They recognize homesickness when they see it.

Home. Nine months in Korea have forced me to redefine that term. At one time 'home' was where my family lived, but as the years have gone by, 'home' has increasingly become wherever I happened to live, family or no. I guess that's the way it goes as you age. Like I said, I miss them, but there is a growing disconnect between missing them and missing 'home.' Perhaps I should redefine "homesickness" as "missing my folks."

In a way, the correct question to ask myself is, "what is the home I will build for myself?" Who will live there with me? I've built quite a nice life here in Busan. I have friends, a good job and all the comforts of modern life added to the opportunity to explore and know a new culture. I joke with Dave that it would take an act of God to keep me here another year, but now I'm not so sure. Korea could be a part of my "home."

The key to making Korea "home" versus just 'that place I happen live' is learning the language. Nothing contributes more to the gulf separating me from the society around me than the silence of words I don't understand. I think when people can't communicate with each other a wall goes up between them and they instinctually distrust one another. It is horribly easy to dehumanize people when the words coming out of their mouth sounds like so much noise.

I think this is really dangerous, and when I come across foreigners complaining about Korea and its customs, I notice a striking correlation between the strength of their bitterness and how much Hangul they speak: Almost none. I have my share of complaints, too, but I put a healthy dose of the blame for those problems on my own misunderstanding of the culture. People miss out on a lot of the magic and knowledge a different society can impart when people hold that society at arms' length. I will be the first to admit that I haven't studied or practiced Hangul as much as I should, but when I do take the time to use what I have learned, I reap some rewards.

Recently, my friend Hyun-jeong sent me a poem she had written in Korean. She had gone to trouble of translating it into English for me, I liked it a lot, and I told her so in an email. I wondered aloud how the poem must be different for people fluent in Hangul, and today she told me why. The poem's title is "Elegy," and I will only give you the first two lines in both English and Romanized Hangul. I'd give you more, but I don't want to embarrass my friend.

Korean: Bee-ga

English: Elegy

Korean: Nay-reen-da

English: Is falling down

An elegy is a poem or song of mourning for someone or something lost. I took these two lines to mean she had lost someone and she was falling down into sadness. However, for a native Korean speaker, the meaning was quite different.

The word "bee" in Korean means "rain." "Ga" is the subject marker. However, if you stick them together they make the word "Bee-ga," which means, "Elegy." The word "Nay-reen-da" is a verb meaning "coming down." So literally, the elegy was falling like the rain. The lines are a metaphor, a play on the word for rain and the word for elegy, built into the structure of the words themselves. That's much more sophisticated than the English translation implies, and I completely missed it.

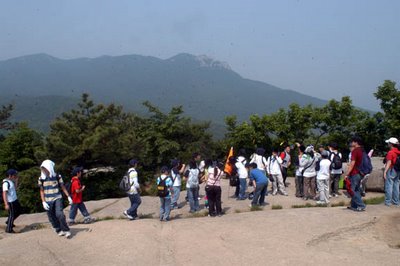

Mr. Kim took the ESS Best Jr. middle school students on an excursion into the mountains. We staffers came along to make sure nobody got eaten by a bear. At seven in the morning some ninety students, Gavin, Dave, all of the Korean teachers and myself converged on the PNU subway stop and began hiking up mighty Kumjangsan, the long ridge north of the city that runs all the way to Beomosa temple.

The girls and boys found their friends, played and chatted with one children from similar social standing until Mr. Kim reshuffled the social deck along academic lines with colored flags denoting class.

Everyone brought a hat and some kids brought sunscreen.

Mr. Yi helped organize the children into an organized mass so they could cross the busy street.

The trail was beautiful, lined in pine trees, mountain laurel (not unlike the laurel in the Appalachians) and big, contented boulders. The way was not so steep until the trail reached the top of the mountain's shoulder. It then pulled back and launched up the steep sides of the ridge.

As Gavin likes to joke, the trails are so steep it's as if they were built by putting a garden hose at the top of the mountain, finding how the water reached the bottom, blazing it and calling it a trail. The Best 2nd and 3 rd-year students went ahead to scout routes and help people, like Ms. Ha (pictured below), over obstacles.

Still, the kids did really well. A few struggled, but by the time they reached the summit, they were just as happy as ever, sitting in the sun and eating candy.

We hiked down to the bottom and regrouped at a campsite for lunch.

Kumjangsan is a major player in the Korean Buddhist tradition, and there was a beautiful gate near the campsite through which we could go down to the restroom by the parking lot.

I had to give another impromptu speech and then we ate lunch. Mr. Kim spoke at length, and introduced some former ESS students who attended the hike with us. Following the hike, Dave, Gavin and I went to Burger King and wolfed down some good old-fashioned junk food.

The next weekend I visited my sister in Japan. Mr. Yi reserved my hotel room and Soo-hoo, my banker at Pusan Bank, got me a cheap ferry ticket courtesy of his girlfriend, who worked at the terminal. For $200 I was going to spend two days and one night in Fukuoka, Japan.

My sister, Sara, was in Fukuoka putting the finishing touches on a minor in Japanese, part of her six-year, duel-degree ordeal as an undergrad at the Georgia Institute of Technology, one of the toughest tech and science schools in the States. My sister is one of my best friends. We've got along famously since we were little, and she is a constant source of love, insight and advice that none but my parents can match. She's also a lot of fun to be around. I love my sister.

I boarded the high-speed KoBee ferry Saturday morning. The Kobee is a hydrofoil, meaning it lowers big wings into the water, turns on a jet-engine, and literally "flies" through the water at sixty to seventy miles-per-hour. We covered the 200 miles between Busan and Fukuoka in three hours. The wings cut through the water like they would have cut through the air. I watched as giant swells rolled towards the ship, but felt nothing at all as the wings sliced effortlessly through them.

I got a great shot of Young-do as the ferry sped away from Busan. That is my apartment complex on the top right under the clouds.

As the hydrofoil approached Fukuoka harbor, suddenly things I took for granted about Japan became very relevant. Holy shit, I thought, my country was at war with this country once. We dropped the only two nuclear weapons ever used in combat on Japan. I reviewed my scant knowledge of Japanese and realized that I only knew two words: "Thank you" and "delicious."

I met my sister and her friend Christ at the foot of my hotel, the Court Clio. They walked me back the way I had come through Hakada station, past the Shinkansen Bullet Train terminal, and down into the subway. Transportation is more expensive in Japan. A simple eight-stop trip to downtown Fukuoka cost $2.50. An all day pass on the train? $6. The bus ride from the ferry terminal to Hakata station? $2.50. Taxis? Don't ask, it'll scare you.

Sara, Chris and I went to lunch with four former members of the program who were on vacation as well as Sara's advisors. One of them, Sensei Naki, had attended my alma mater, the University of Georgia, and we reminisced on Athens. She was part of a band while studying there. She took us to a sushi restaurant with big tanks of fish and crustaceans in the middle of it.

The food was exquisite, both in taste and in price, though $17 for a lunch like we ate is actually pretty cheap, I was told. The table across from us ordered a fish, and when it arrived, sliced thin and pinned to the plate with a wooden stick, I noticed that the tail was still twitching as the life ebbed from it's expertly-prepared flesh. I imagined watching something eat slices of me as my conscienceness slowly fell away into darkness.

Hunter, one of Sara's friends, spent the better part of a half-hour telling me about other, less disturbing, aspects of Japanese cuisine, such as the junk food.

"You can't be told about Japanese junk food," he said. "You must try it."

I got my chance later that night when we went out for Japanese-style pizza (pronounce it with no "t" sound) and "Yakisoba," which looked liked noodle-stirfried with Rice Krispies and was outstanding.

That night we went out to a Karaoke bar. Sara and the others sang a wide variety of Japanese pop songs, and a few songs that made no sense at all, but were fun to sing. They were a fun group of people, and I liked how they were so positive about Japan. One of them, Chris, is going to work there for six months following the end of the program in July.

Throughout the journey, I couldn't help but compare Korea to Japan. Given how close the countries are geographically and how contentious their relationship is, was, and probably will be for a long time to come, I couldn't help myself. Structurally, there were many similarities. The sidewalks had "blind walks" in them: braille for feet. People rode bikes and scooters everywhere.

Everyone was very friendly, just like in Korea.

However, there were fewer people who could speak English to me in Fukuoka than in Korea, which frankly surprised me. I figured Japan, with it's closer ties to The States, would have had a stronger English presence. I was wrong, and if it hadn't been for my sister, I would have been in a trouble. She speaks very good Japanese, and could do things in the language I can't do in Korean, such as get directions and express her opinion. She and Christ were constantly talking to each other in Japanese.

Japan is by and large the cleanest place I have ever visited. There is no weird smell. There is no trash on the streets. The buildings are taller and their architecture is very consistent. The cars all drive on the left side of the road, which is strange, but they drive slowly and obey the traffic lights. What's more, the bus drivers in Japan are very polite, as well. All in all, however, Fukuoka reminded me of a big, cosmopolitan American city like New York or San Francisco.

No one stared at me in Japan. In Korea, people are constantly staring at me like they've neverr seen an American in their whole life. Not Japan. There doesn't seem to be anything compelling about white people in Japan. That's fine with me.

There were bums everywhere in Japan, setting up homes made of cardboard in Hakata Station. I even saw one plugging in a cell phone to charge as I walked back to my hotel Saturday night.

It was good to see my sister in such high spirits. We had fun, and I can't wait for July 8th when she comes to Korea for a week. Can anyone say "culture shock?" Anyway, I've written enough. I'll keep you guys up to date as much as possible the next few week. I have a new Korean friend, and she is teaching me all about the culture, history and beliefs in Korea. I think she'll bring a fresh perspective to SoKoNotes. Until next time! Peace. --Notes

3 comments:

Hi Notes,

I've followed your blog for quite some time and always try to post comments. I don't know you.. I'm just another random person on the internet. Also, I'm in the United States and have never been to S. Korea, but I read your blog anyways.

Anything you do is gold... whether it be photography or writing, so update when you have time and when you feel like it. I'm sure many people enjoy reading this blog. Take care :)

I think this is the power of journalism. To make people have second hand experience. And you really open people's eyes to the unknown. I wish I could do that. But maybe it's easier just to help you do that than to do it on my own. So I'll always be there for you and try to make you catch up new things around my world.

I hope I can support you.

Fantastic post. (Just another note, though: one "speaks" "hangukmal"; one writes or reads "hangul." Hangul is the script, not the language.)

Anyway, I really enjoyed this post. You write eloquently, and I competely identify with your feelings about the language barrier and its relation to whether one feels at home.

Post a Comment